Macro Crossroads | China’s Economy in 2026: Slower, yet Bigger and More Global

29.01.2026

Prof. Zhu Ning

Macro Crossroads is a column by Prof. Zhu Ning, Senior Macro Strategist at Primavera Capital Group. In this series, he offers perspectives on the macroeconomic trajectory of China and the global economy, technological and industrial developments, and key policy shifts.

China’s economy has headed into 2026 sending mixed messages. On one side, the sudden rise and success of Deep Seek, Manus and other domestic AI leaders have boosted confidence in China’s ability to both drive innovation and commercialize leading-edge technologies. On the other, national real estate prices are still declining, further extending a prolonged drag on confidence and consumption levels.

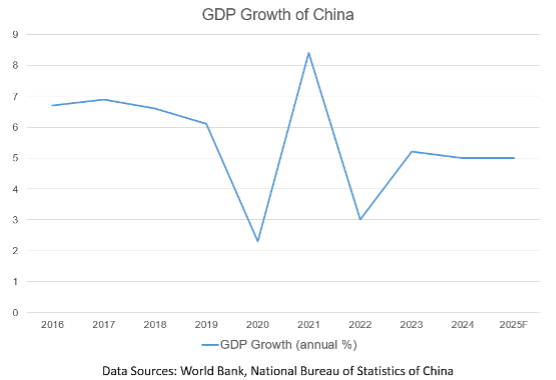

With the country’s economic growth target most likely to be set at “about 5 percent” once again in 2026, China’s economy will probably expand at an even slower pace in 2026 compared to 2025. A key factor in this is exports, as last year the economy benefited from a stronger-than-expected surge in export demand, which may not be repeated over the coming twelve months.

What remains misunderstood, however, is that the economy has been allowed to grow at a slower pace not because Chinese policymakers disregard economic growth, but because innovation, national security and a “sustainably reasonable” growth rate have replaced maximum GDP expansion as the top policy priorities. Put differently, the growth trajectory of the economy continues to be directed by the government and is set to proceed at a slower pace, as policymakers deem this more sustainable and appropriate for achieving their wider goals.

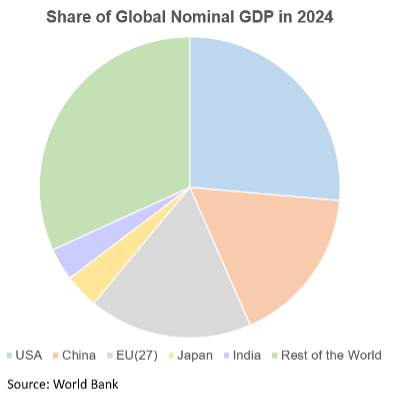

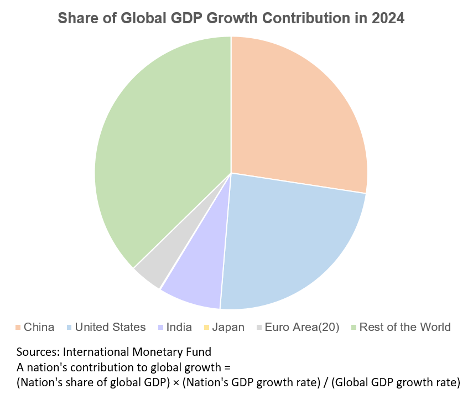

At the same time, many fail to notice that even at about 5 percent, which is roughly half the growth rate in 2008, China’s overall economy in 2026 is four times larger in comparison. To get a better sense of scale through an example, China’s economy in 2008 was still in the range of German-sized economies, which was the fourth largest globally at the time. Fast forwarding to today, China’s GDP is roughly four times the size of the current German economy. Even with a slower growth rate, China’s contribution to global economic growth remains comparable in scale to that of India and the United States combined, the second and third largest contributors.

The sustained growth of China’s economy means that the country naturally benefits from a growing share of almost every sector of the global economy, even when growth rates are more moderate. The scale of China’s market also affords it greater leverage in shaping the global economic order, including tariff negotiations, technology affairs, and commodities and mineral trade relations. Against this backdrop, it remains likely that the world will see more frequent and intense exchanges between China and the U.S. in an apparent shift towards an increasingly G2 dynamic.

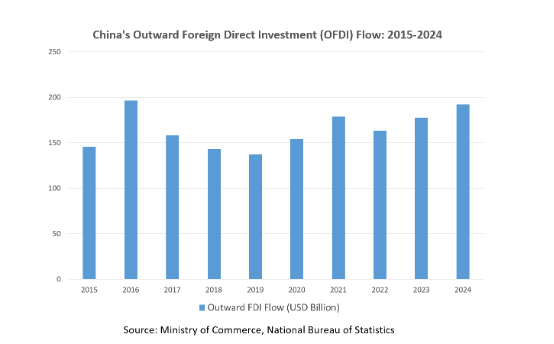

One of China’s unique advantages is its unrivaled manufacturing sector and indispensable supply chain networks. China’s ability to supply the world with face masks and ventilators during the peak of Covid, for example, demonstrated that China’s economy represents much more than just impressive growth statistics. With strong encouragement and incentives to go abroad following the pandemic, China is, in some ways, emulating Japan’s strategy after the peak of its own real estate bubble: building another Japan outside Japan.

A key difference may be China’s increasing ambitions and global clout. China has long advocated for the Global South to have a greater role in world affairs, and has emerged as one of its leading voices. With its burgeoning economy and long-term need for energy and natural resources, China has been focusing on cultivating its relationships with the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America. Many countries in these regions are on the cusp of their own industrialization. China’s unprecedented manufacturing prowess, supportive financing commitments, and shared development experience together create a valuable foundation for closer partnerships and economic connectivity. Heading into 2026, it is becoming increasingly clear that even as China’s own growth moderates, significant value will be created as it focuses on building another China, outside China.

If you have any questions or topics you would like Prof. Zhu to explore on China and the global macro economy, please write to macro@primavera-capital.com. Selected questions will be addressed in future columns.

About Prof. Zhu Ning

Ning is Senior Macro Strategist at Primavera Capital Group and Professor of Finance at the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance (SAIF), Shanghai Jiao Tong University. A top expert on behavioral finance and the Chinese economy, he is a member of the Academic Committee of the China Capital Market Society. Previously, Ning held senior positions at Lehman Brothers and Nomura Securities. He is the author of The Enemy of the Investor, The Friend of the Investor, and China’s Guaranteed Bubble. Ning holds a bachelor’s degree from Peking University and a Ph.D. from Yale University.