Fred Hu: The demographic dividend has not disappeared, and the encouragement of childbirth cannot go astray

24.03.2023

Abstract: Pragmatism is the key reason for China’s sustained economic development.

Introduction:

On the morning of March 13, after the closing of the 14th National People’s Congress, in response to a reporter’s question about whether China’s demographic dividend is disappearing, Premier Li Qiang said that the demographic dividend depends not only on the quantity of the population, but also on the quality of the population, and not only on the number of people but also on the number of talents. China’s current population of working age is nearly 900 million people, with 15 million new laborers added each year, and the abundance of human resources is still a significant advantage for China. What’s more, China’s population with higher education has exceeded 240 million, and the average number of years of education for the new labor force has reached 14 years. China’s demographic dividend has not disappeared, and its talent dividend is gradually taking shape.

Two years ago, when the 7th census was completed and the theory of the ending of China’s demographic dividend was rampant, Dr. Fred Hu, founder of Primavera Capital Group, wrote an article stating that China’s demographic dividend had not disappeared and that, at the same time, China’s economic development was more dependent on the talent dividend. On top of this topic, this paper puts forward several core arguments:

- China’s economic development will depend on the improvement of the quality of the population, not just the growing number of people;

- Consumption upgrades and technological innovation will continue to drive economic growth;

- One should not go on advocating more births and promoting the economy when people’s quality of life is not guaranteed.

It should be noted that, based on long-term, forward-looking, in-depth research, we have two propositions when it comes to answering such major economic questions as demographics:

- Avoid simplifying complex issues, but keep it simple to start with and think from multiple angles;

- Respect logic and common sense; people are the ends, not the means.

Pragmatism is the key reason for China’s sustained economic development.

The following is the text.

*This previously published article has been tweaked, including revisions to the real-time data.

In May 2021, right after the release of the results of the 7th national census, the three-children policy was introduced, making the demographic transition a hot topic of public discussion. We have heard a lot of discussions recently – “the demographic dividend is disappearing” and “financial subsidies should be used to encourage childbirth”. While it should be acknowledged that these discussions have facilitated rapid government action, it should also be noted that the discussions have both a tendency to simplify the relationship between demographics and economic growth and revealed a worrisome way of thinking.

There should be a basic starting point for discussing public policy: economic development is for people to live happier and freer, and we cannot, in turn, regard the means as the goal and advocate more children to promote economic development while the quality of life is not ensured. Social development should respect the laws of nature and the freedom of individual choice. To tackle demographic issues, the government should play a role from the perspective of providing public goods.

Has the demographic dividend disappeared?

A demographic dividend is usually defined as a larger share of the working-age population in the total population, a lower social dependency burden, and demographic conditions favorable to economic development.

There is a tendency for many people to simplify the relationship between demographics and economic growth when discussing the demographic dividend. However, the fundamental reason for China’s economic takeoff over the past four decades is that reform, opening-up and entrepreneurship have mobilized people, allowing capital and technology to work and unleash economic potential. Demographics was one of the key production factors that were activated in this process.

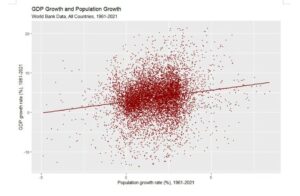

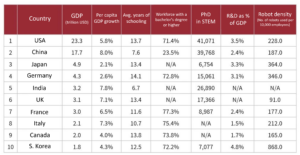

Figure 1: The relationship between GDP growth rate, per capita GDP growth rate, and population growth rate in various countries around the world from 1961 to 2021. The GDP growth rate was slightly positively correlated with population growth rate. Per capita GDP and population growth rate were negatively correlated slightly. The impact of population growth on economic growth is a topic of much debate among economists, and it is undoubtedly difficult to draw a simple conclusion about the relationship between population and economic growth. (Data source: World Bank)

Figure 1 shows that total GDP is slightly positively correlated with population growth, but GDP per capita and population growth are negatively correlated. The effect of population growth on economic growth is a topic of endless debate among economists, and there is no doubt that the relationship between population and economic growth should not be simply concluded.

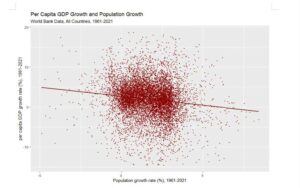

There is a view that the demographic dividend is the basic, root cause of economic growth. As to whether this view is valid, let’s examine it with data. 2019 data show that the populations of India and Africa are over 1.3 billion and nearly 1.4 billion respectively, and as can be seen from Figure 2, the demographics of these two regions are also younger than China’s. However, the total GDP of both India and Africa is less than one-fifth of that of China, the economic growth rate of Africa is almost half of that of China, and the economic growth rate and development results of these two regions are not better than those of China. [1] Thus, it is clear that the relationship between population and economic growth is very complex, and the idea that a decline in the size of the working population will lead to slower economic growth is debatable.

Figure 2: Demographic structure of China, India and Africa in 2023 (Source: PopulationPyramid.net)

Figure 3: Top 10 countries with the fastest growing populations and their GDP per capita growth rates in 2021 (Source: World Bank data)

China’s population problem is not as pessimistic as it is made out to be if we shift the perspective from the absolute quantity of the population to the structure and quality of the population:

- In terms of quantity, according to data released in the 7th National Population Census, the population of labor force aged 16 to 59 has decreased by more than 40 million compared to the 6th National Population Census. However, the total size of the labor force population is still large, reaching 880 million people. From a global perspective, the labor force resources in China are still abundant.

- In terms of quality, the average length of education for the labor force aged 16 to 59 has reached 10.75 years, which is 1.08 years higher than the 9.67 years in 2010. The population with a high school education or above has reached 385 million, accounting for 43.79%, which is 12.8 percentage points higher than in 2010. Hence, people can see that the quality of the population is also improving.

- In terms of productivity transformation, compared to the 6th Census, data from the 7th Census show that as the urban population further concentrates in the eastern coastal provinces and cities, the labor force has moved to industries with higher productivity, and the human resource structure has been further optimized.

Some people simply believe that if population growth slows and fertility rates decrease, the Chinese economy will not be able to maintain its previous growth momentum. My view is exactly the opposite. China’s economic development relies on the improvement of the population’s quality, not just the growth of the size of the population. I call this the talent dividend.

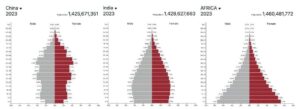

Figure 4: The correlation between human capital and productivity. 53 countries in Panel A include both OECD and non-OECD countries. panel B shows data for OECD countries, including the years 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, 2005, 2008, 2011, 2014, 2017 and 2020.

A 2022 OECD Working Paper study shows that there is a positive correlation between human capital (measured by average years of education and PISA test scores) and productivity. The impact of education level on human capital is 3-4 times greater than that of education years. This result clearly demonstrates that the economic dividend can be obtained by improving the level of talent.

Future drivers of China’s economic growth

The contribution of labor force to productivity depends not only on the quantity, but more importantly, on the quality of the labor force. That is the talent dividend. The popularity of education, the improvement of labor force quality, and the optimization of human resource structure can all offset the pressure caused by the decline of the absolute quantity of labor force.

Automation in China’s manufacturing industry is accelerating. The number of robots per 10,000 employees in manufacturing is growing rapidly, with some reports showing that China’s robot density (number of robots per 10,000 employees) has reached 187, which is higher than the global average of 113 [3]. The automation and digitization of industries can replace repetitive and inefficient labor, and high-quality labor can then be transferred to positions that are more valuable to economic growth, thus bringing out human creativity.

Throughout the decades that I’ve spent working in the investment sector, I’ve always focused on the economic growth opportunities brought about by consumption and technological innovation. These have been the core drivers of China’s economic growth over the past decade, and they are the core logic of our investment strategy. Today, I still believe in this assessment, and China’s demographic trends have not weakened these two core drivers.

Figure 5: Data for the world’s top 10 economies. The data show that China has a lot of potential to improve its human capital. The STEM doctoral degree data are from 2018, the robotics density data from 2019, R&D as a percentage of GDP from 2020, and the rest from 2021.

Technology: There is no doubt that China’s future economic growth will depend on technological progress and innovation. We also need to improve the quality of population behind this assumption. When the overall population quality is improved, China can produce more top-notch, innovative and creative talents. Throughout the human history, regardless if they are basic research discoveries, technological application inventions, or model innovations, all these intellectual sparks have been transformed into huge productivity. According to China’s Ministry of Science and Technology, the contribution of scientific and technological progress to China’s economic growth has exceeded 60% in 2020. [4]

Therefore, the 14th Five-Year Plan and the outline of the 2035 Vision put a prominent emphasis on improving the population quality, proposing to build a high-quality education system, and an all-round and comprehensive health system. The government strives to optimize the population structure, expand the population quality dividend, and improve human capital and people’s capacity for all around development.

Consumption: The more underlying growth momentum behind consumption comes from urbanization and GDP per capita growth.

Looking at the 7th Census figures, China’s urbanization rate is now about 64%, while the true urbanization rate of the household population is only 45%. The UN’s Urbanization Prospects predicts that China’s urbanization rate is expected to reach 80% in 2050, close to the level of the U.S. today. From more than 60% to 80%, there is still 20% of the room for growth, which is translated into over 200 million new urban population, close to another U.S.

Of course, the next phase of China’s urbanization should pay more attention to the quality. Simple and crude urbanization by merely building roads and tall buildings has limited drive for economic growth. Sustainable urbanization should improve public services ranging from the environment to education, health, and medical services. It should aim to improve people’s quality of life and bring about more happiness.

The growth in GDP per capita is the underlying support for the consumer boom. China’s GDP per capita has just exceeded US$10,000, still a long way to go to catch up with other economies such as the U.S. and Japan. With adequate food and clothing, consumption of products, services, entertainment and culture is expected to become more diversified and richer. This richness and diversity can be reflected both in consumption upgrading and in consumption grading.

Looking at investment from a demographic perspective requires deeper analysis

After the release of the 7th Census data, we have seen some discussions on related concepts of economy such as the gray-hair economy and the singles economy. Investing solely based on emerging concepts risks making short-sighted decisions. I prefer to focus on forward-looking and long-term drivers while paying attention to the fundamental factors underlying short-term social phenomena.

From a macroeconomic perspective, urbanization and GDP per capita growth are both the underlying causes of demographic change and the more fundamental, essential trends that we focus on. This gives rise to fundamental investment opportunities including the upgrading of consumption and services, low-carbon transformation, and technological innovation.

In the consumer and services sector, we have noticed the rise of a new generation of consumers. Their consumption patterns are based on their interests, aesthetics, value propositions, and knowledge-based content, fueling a number of new consumer brands and disrupting the traditional landscape. There is a rising demand for features, quality, and services, intensifying market competition. They have led to opportunities for industry consolidations and reorganizations, which are particularly evident in the multinational consumer goods sector.

There is a contradictory tension between the need for more energy and the need for a greener environment after urbanization and rising per capita income. Such tension must be resolved through a low-carbon transition.

Climate change poses a huge challenge to mankind. While the global low-carbon transition faces a huge funding gap, it also offers tremendous investment opportunities. According to Goldman Sachs’ research, achieving China’s 2060 carbon neutrality target will require US$16 billion of investment in clean technology facilities, creating 40 million jobs, and driving economic development. [5] Capital participation in carbon neutral investment is an investment in the future that can yield lucrative returns. More importantly, reshaping a clean industry supply chain through the power of capital will benefit China’s energy security and the living environment.

Many new opportunities have emerged under the topic of carbon neutrality. Apart from the widely sought-after new energy end-user products like electric vehicles, we should also pay attention to the trends in the entire energy supply chain, including upstream capacity, energy storage, transmission, new green industries, and new energy-saving and emission reduction technologies. Both the supply and demand sides of energy are in urgent need of upgrading, and significant opportunities are brewing.

People are not tools. The encouragement of childbirth cannot go astray

With industrialization and economic development, demographic changes such as declining birth rates are inevitable. From the perspective of economic development, I argued about a decade ago that those who thought liberalizing the birth restriction policy would usher in a new wave of baby boom in China would fall flat. Factors like increased female labor force participation rates, inadequate childcare facilities, and high costs of education and housing will all affect the actual effects of the relaxation of population control policy. There are also complex social issues involved.

I don’t agree with the argument of putting more psychological pressure on women and young people, as if they are accountable for the problems of China’s economic development. It is ridiculous in my opinion as it’s like putting the cart before the horse. Economic development should make people happier, freer, and realize their self-worth. We should not make the means as our goals by encouraging childbirth in order to promote economic development when the quality of life is not guaranteed.

It is also questionable that financial subsidies can effectively incentivize childbirth. The atomization of society, the lagging of social services, and the evolving self-awareness of people are all factors besides income that constrain birth rate. If we recognize the future economic development will be driven more by population quality instead of the absolute quantity, we should invest our limited resources in education and scientific research.

Judging from the experience of developed countries, it is not advisable to be overly confident in the effects of stimulus policies. The general rule around the world is that as GDP per capita grows, education levels and job opportunities would rise, women would have more choices, and the natural birth rate of the demographic tends to decline. We need to respect the laws of nature and an individual’s freedom of choice by abandoning the idea of social engineering. The Chinese people have a lot of wisdom and will not refuse to have children if the conditions are good. If the government wants to accomplish something in this area, it should prioritize approaching it from the perspective of public goods by proving better education, living environment, and health care to its people.

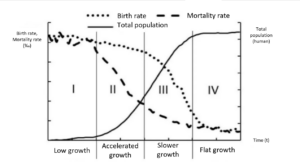

Figure 6: The four stages of the demographic transition. (Source: People’s Bank of China Working Paper No.2021/2 “Understanding and Responses to the Demographic Transition in China”)

Social science research shows that demographics tend to go through four stages of transition as societies develop: “low growth (I) – accelerated growth (II) – slowing growth (III) – low growth (IV)”, such is the natural law of social development[6]. We are certainly concerned about the demographic transition and the decline in birth rate, but we do not see it as a crisis. As long as China continues to promote reform, openness, innovation, and continues to invest in education, science and technology, and human capital, the Chinese economy will be able to grow at a relatively fast and sustainable pace, with at least another 20 to 30 years of golden age of development.

In 2015, I called for the following: In the next two or three decades, what will drive China’s development is not how many people are born, but whether the government can continue to promote reforms in all aspects. Currently, it seems that reforms in the Hukou system, housing, education, etc., have become more urgent issues from the perspective of driving population growth.

On March 13, 2023, two years after this article was published, the new government administration pointed out that China’s talent dividend is gradually taking shape. It also stated that it would conduct in-depth analysis and assessment of the possible problems brought by population growth and decline, and actively respond to them. I am glad to see that the central government is speeding up the formulation of policies. The next issue that deserves more attention is what supporting policies have be introduced and actually be implemented.

[1] IMF Datamapper, looking at total GDP in 2020, China is $14.7 trillion, Africa is $2.4 trillion, and India is $2.7 trillion, with the average annual GDP growth rates of 7.2% for China, 5.6% for India, and 3.4% for Africa over the 2010-2020 period.

[2] National Bureau of Statistics, Main Data of the 7th National Population Census

[3] International Federation of Robotics, Robot Race: The World’s Top 10 automated countries, 2021

[4] Minister of Science and Technology Wang Zhigang, State Information Office Press Conference, Feb. 26, 2021

[5] Goldman Sachs Equity Research, Carbonomics China Net Zero: The clean tech revolution, 2021

[6] PBOC Working Paper No. 2021/2 “Understanding and Responses to China’s Demographic Transition.”